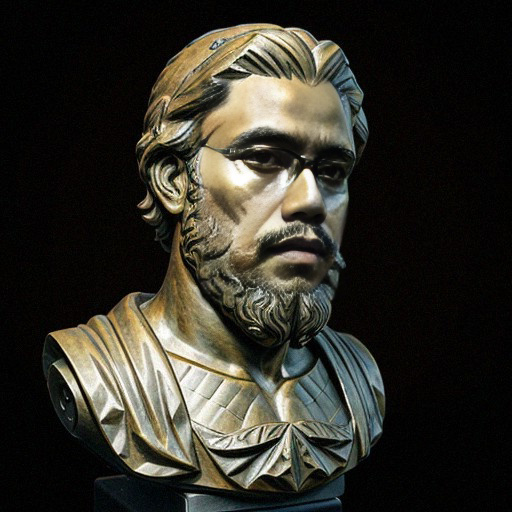

Universalism: Hegel

As far as I am investigating, Hegel never discusses the concept of universalism in particular. In a lecture he tries to deduce from the essence of his philosophy;

He tried to exhibit their (this series of spiritual configurations) necessary procession out of one another, so that each philosophy necessarily presupposes the one preceding it. Our standpoint is the cognition of spirit, the knowledge of the idea as spirit, as absolute spirit, which as absolute opposes itself to another spirit, to the finite spirit. To recognize that absolute spirit can be for it is this finite spirit’s principle and vocation. (LHP 1825–6, III: 212).

In my opinion the best way to know Hegel’s concept of universalism is by searching for his explanation in key concepts in his philosophy, including; absolute spirit, philosophy of history, Christian outlook, philosophy of religion, philosophy of history, self counsiousness, phenomenology of spirit, and logic. Here’s the quote;

Universalism in Cristianity

There is much that can be found in Hegel’s writings that seems to support this view. In his lectures during his Berlin period one comes across claims such as the one that philosophy “has no other object but God and so is essentially rational theology” (Aes I: 101). Indeed, Hegel often seems to invoke imagery consistent with the types of neo-Platonic conceptions of the universe that had been common within Christian mysticism, especially in the German states, in the early modern period. The peculiarity of Hegel’s form of idealism, on this account, lies in his idea that the mind of God becomes actual only via its particularization in the minds of “his” finite material creatures. Thus, in our consciousness of God, we somehow serve to realize his own self-consciousness, and, thereby, his own perfection. In English-language interpretations, such a picture is effectively found in the work of Charles Taylor (1975) and Michael Rosen (1984), for example. With its dark mystical roots, and its overtly religious content, it is hardly surprising that the philosophy of Hegel so understood has rarely been regarded as a live option within the largely secular and scientific conceptions of philosophy that have been dominant in the twentieth century.

Universilism in History

An important consequence of Hegel’s metaphysics, so understood, concerns history and the idea of historical development or progress, and it is as an advocate of an idea concerning the logically-necessitated teleological course of history that Hegel is most often derided. To critics, such as Karl Popper in his popular post-war The Open Society and its Enemies (1945), Hegel had not only advocated a disastrous political conception of the state and the relation of its citizens to it, a conception prefiguring twentieth-century totalitarianism, but he had also tried to underpin such advocacy with dubious theo-logico-metaphysical speculations. With his idea of the development of spirit in history, Hegel is seen as literalising a way of talking about different cultures in terms of their spirits, of constructing a developmental sequence of epochs typical of nineteenth-century ideas of linear historical progress, and then enveloping this story of human progress in terms of one about the developing self-conscious of the cosmos-God itself.

Universalim in Absoluty Spirit

Hegel, according to this reading, postulated a form of absolute idealism by including both subjective life and the objective cultural practices on which subjective life depended within the dynamics of the development of the self-consciousness and self-actualisation of God, the Absolute Spirit`

Universality in Phenomenology of Spirit

In Hegel, the non-traditionalists argue, one can see the ambition to bring together the universalist dimensions of Kant’s transcendental program with the culturally contextualist conceptions of his more historically and relativistically-minded contemporaries, resulting in his controversial conception of spirit, as developed in his Phenomenology of Spirit. With this notion, it is claimed, Hegel was essentially attempting to answer the Kantian question of the conditions of rational human mindedness, rather than being concerned with giving an account of the developing self-consciousness of God. But while Kant had limited such conditions to formal abstractly conceived structures of the mind, Hegel extended them to include aspects of historically and socially determined forms of embodied human existence.

Universality self-consciousness

It is thus that Hegel has effected the transition from a phenomenology of the individual’s subjective mind to one of objective spirit, thought of as culturally distinct objective patterns of social interaction to be analysed in terms of the patterns of reciprocal recognition they embody. (“Geist” can be translated as either “mind” or “spirit”, but the latter, allowing a more cultural sense, as in the phrase “spirit of the age” (“Zeitgeist”), seems a more suitable rendering for the title.) But this is only worked out in the text gradually. We—the reading or so-called phenomenological we—can see how particular shapes of self-consciousness, such as that of the other-worldly religious self-consciousness (Unhappy Consciousness) with which Chapter 4 ends, depend on certain institutionalised forms of mutual recognition, in this case one involving a priest who mediates between the self-conscious subject and that subject’s God. But we are seeing this “from the outside”, as it were: we still have to learn how actual self-consciousnesses could learn this of themselves. So we have to see how the protagonist self-consciousness could achieve this insight. It is to this end that we further trace the learning path of self-consciousness through the processes of reason (in Chapter 5) before objective spirit can become the explicit subject matter of Chapter 6 (Spirit).

the path of liberation for the spiritual substance, the deed by which the absolute final aim of the world is realized in it, and the merely implicit mind achieves consciousness and self-consciousness. (PM: §549)

Universality in Term of Logic

Hegel’s later treatment of the syllogism found in Book 3, in which he follows Aristotle’s own three-termed schematism of the syllogistic structure, repeats this triadic structure as does his ultimate analysis of its component concepts as the moments of universality, particularity, and singularity.

Book 3, The Doctrine of Concept, effects a shift from the Objective Logic of Books 1 and 2, to Subjective Logic, and metaphysically coincides with a shift to the modern subject-based category theory of Kant. Just as Kantian philosophy is founded on a conception of objectivity secured by conceptual coherence, Concept-logic commences with the concept of concept itself, with its moments of singularity, particularity and universality. While in the two books of objective logic, the movement had been between particular concepts, being, nothing, becoming etc., in the subjective logic, the conceptual relations are grasped at a meta-level, such that the concept concept treated in Chapter 1 of section 1 (Subjectivity) passes over into that of judgment in Chapter 2. It is important to grasp the basic contours of Hegel’s treatment of judgment as it informs his subsequent treatment of inference.

The philosophy of subjective spirit passes over into that of objective spirit, which concerns the objective patterns of social interaction and the cultural institutions within which spirit is objectified. The book entitled Elements of the Philosophy of Right, published in 1821 as a textbook to accompany Hegel’s lectures at the University of Berlin, essentially corresponds to a more developed version of the philosophy of objective spirit and will be considered here.

Universalism in Philosophy of History

The final 20 paragraphs of the Philosophy of Right (and the final 5 paragraphs of objective spirit section of the Encyclopaedia) are devoted to world history (die Weltgeschichte), and they also coincide with the point of transition from objective to absolute spirit. We have already seen the relevance of historical issues for Hegel in the context of the Phenomenology of Spirit, such that a series of different forms of objective spirit can be grasped in terms of the degree to which they enable the development of a universalizable self-consciousness capable of rationality and freedom. Hegel was to enlarge on these ideas in a lecture series given five times during his Berlin period, and it was via the text assembled on the basis of these lectures by his son Karl, that many readers would be introduced to Hegel’s ideas after his death.

The final 20 paragraphs of the Philosophy of Right (and the final 5 paragraphs of objective spirit section of the Encyclopaedia) are devoted to world history (die Weltgeschichte), and they also coincide with the point of transition from objective to absolute spirit. We have already seen the relevance of historical issues for Hegel in the context of the Phenomenology of Spirit, such that a series of different forms of objective spirit can be grasped in terms of the degree to which they enable the development of a universalizable self-consciousness capable of rationality and freedom. Hegel was to enlarge on these ideas in a lecture series given five times during his Berlin period, and it was via the text assembled on the basis of these lectures by his son Karl, that many readers would be introduced to Hegel’s ideas after his death.

World history is made up of the histories of particular peoples within which spirit assumes some “particular principle on the lines of which it must run through a development of its consciousness and its actuality” (PM: §548). Just the same dialectic that we have first seen operative among shapes of consciousness in the Phenomenology and among categories or thought-determinations in the Logic can be observed here. An historical community acts on the principle that informs its social life, the experience and memory of this action and the consequences it brings—a memory encoded in the stories that circulate in the community—results in this principle becoming available for the self-consciousness of the community, thus breaking the immediacy of its operation. This loss of immediacy brings about the decline of that community but gives rise to the principle of a new community: in rendering itself objective and making this its being an object of thought, [spirit] on the one hand destroys the determinate form of its being, and on the other hand gains a comprehension of the universal element which it involves, and thereby gives a new form to its inherent principle … [which] has risen into another, and in fact a higher principle. (PWH: 81)

It is thus that “the analysis of the successive grades [of universal history] in their abstract form belongs to logic” (PWH: 56), but once more, it must be stressed that, as with philosophy of nature, philosophy of history is not meant to somehow magically deduce actual empirical historical phenomena, like Krug’s pen; rather, it takes the results of actual empirical history as its material and attempts to find exemplified within this material the sorts of categorial progressions of the logic. Thus the activity of the philosophical historian presupposes that of “original” and “reflective” historians (PWH: 1–8). The actual world is full of contingencies from which empirical historians will have already abstracted in constructing their narratives, for example, when writing from particular national perspectives. To grasp history philosophically, however, will be to grasp it from the perspective of world-history itself, and this provides the transition to absolute spirit, as world history will understood in terms of the manifestation of what from a religious perspective is called “God”, or from a philosophical perspective, “reason”. Hegel clearly thinks that there is a way of cognitively relating to history in a way that goes beyond the standpoint of consciousness and the understanding—the standpoint of what we now think of as informing scientific history. From the perspective of consciousness history is something that stands over against me qua something known, but from the standpoint of self-consciousness I grasp this history as the history of that which contributes to me, qua rational and free being.

Philosophy proper only thrives under conditions of at-homeness in the world and such conditions obtained in neither the Roman nor medieval world. Hegel then sees both periods of philosophy as effectively marking time, and it is only in the modern world that once more develops. What modern philosophy will reflect is the universalization of the type of subjectivity we have seen represented by Socrates in the Greek polis and Jesus in the Christian religious community. Strangely, Hegel nominates two very antithetic figures as marking the onset of modern philosophy, Francis Bacon and the German Christian mystic, Jacob Böhme (LHP III: 170–216). In the 1825–6 lectures, from there Hegel traces the path of modern philosophy through three phases: a first period of metaphysics comprising Descartes, Spinoza and Malebranche; a second treating Locke, Leibniz and others; and the recent philosophies of Kant, Fichte, Jacobi and Schelling. Of course the perspective from which this narrative has been written is the absent final stage within this sequence—that represented by Hegel himself. Hegel concludes the lectures with the claim that he has

===============================================================================

Universalim: Michel Foucault

If we look for the concept of Foucault’s universalism, then we will get a negative meaning. This philosopher as far as I am concerned does not build the concept of universalism positively. Foucault as one of the pioneers of the trend of postmodernism criticizes individual efforts, ideology, science, religion that builds universalism. Tendesi concept of knowledge and power, explain the occurrence of power is not konensional. He comes from anywhere, not always from conventional meanings such as bureaucracy and party. Power can not be defined but operate wherever. Freedom always accompanies the truth. There is no linearity in meaning. Meaning always created, he comes at random. Foucault’s nominism tendency resides in the way he sees everything, which can be counteracted with the essentialist. With regard to Foucault’s view of universalism, it can be said briefly that Foucault is as follows.

Foucault was firmly and consistently opposed to the notion of universal categories and essences, ‘things’ that existed in unchanged form in all times and places such as the State, madness, sexuality, criminality and so on. These things only acquire a real (and changing) existence as the result of specific historical activities and reflection.

==================================================================================

Universalism: Edward Said

I get an explanation of Edward Said’s view of the universalism of the article in a journal entitled, “Edward Said’s Universalism, The Perspective of the Margins” is written by; Bernd M. Scherer. Edward made an attempt to critique the misappropriation of the concept of universalism by the west as opposed to criticizing the concept of universalism itself. Here’s the summary I quote from the article.

Universalism of the West that became a chief object of attack by many postcolonial thinkers. They castigated Western arrogance, and usually countered it with cultural-relativistic approaches which held that there is no single truth or universal value(s), arguing that these arise from context, dependent on the respective historical situation of a particular society.

Edward Said is counted among these postcolonial thinkers, he surprises us, upon closer reading, with a universalistic stance. He demands universal standards, as these provide the only basis for the indictment of injustice in the world, and for the restoration of rights to the disenfranchised (i.e., see Representations of the Intellectual (1994)). In Said’s view, the absence of a universal standard opens the door for the legitimization of many local injustices.

Accordingly, when Said attacks the West for casting itself as the representative of universal values, this attack is aimed not at universalism itself, but rather, at the way in which the West deals with it. Said follows three lines of argumentation in breaking the spell of the Western position:

a) The West uses universalism to distance itself from other—for example, Muslim—societies. According to the Western position, it represents universal reason, whereas in these other societies, chaos and irrationalism reign. In other words, universalism, here, is abused as part of a culturalistic strategy of exclusion.

b) The universalistic position plays a role in power strategies that are designed to advance specific interests. For example, where addressing human rights violations coincides with other interests of the West, the latter intervene. Where it does not, it turns a blind eye to the injustice.

c) The first two points reveal that the mere reference to a universalistic position cannot in itself legitimize concrete action, as the universal statement is an “all” statement—one that is valid for all cases. Since it is never possible to take all cases into account, however, such statements are, in fact, only selectively applied. This in turn opens the door to political, social, and other interests that eventually must be expressed through concrete action. Therefore, the generality of the universalistic position cannot be justified in itself, alone, but only in connection with concrete action. For Said, this concrete action means advocating for the weakest members of society; those who are outcast and marginalized. Only when the weak are given a voice, only when the oppressed are listened to, is the universalistic claim redeemed. And only then does it become experienceable in the minds of those affected.

Said grounds universalism. He reconnects it with its material basis, so as to wrest it from the power interests to which general reason sees itself subjected. This is also why he favors space over time and why he is more interested in the geographical than the historical. It is in space that the concrete struggle is waged, the struggle that demands that we take a stand. Time, though, allows reflection. In time, concrete action is translated into the generality of thinking.

The debate around Said’s interpretation of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park (Said 1994) is of interest in this context. According to Said, Austen, as a sensitive analyst of her time, cannot avoid portraying the colonial situation in the West Indies as one of the bases of England’s wealth, and thereby depicting human oppression and marginalization. These are inherent features of the geography of nineteenth-century England. Later writings on literary history have treated them as marginal phenomena. Said challenges this. He argues that only when we broaden our view to take in this seemingly peripheral situation—the oppression and exploitation of the nameless—do we come to understand the logic and structure of society. And this is not unique to the specific circumstances of colonialism in the West Indies in the nineteenth century. It is also true of, for example, the situation of Palestinians today. We owe this “new accounting of the world” to Edward Said. He draws our attention to the blind spots generated by our categorical apparatus.

Said’s sociopolitical experience and commitment, in turn, must be attributed to the situation of the Palestinians, especially after 1967, when Israel occupied what remained of the Palestinian territories: Gaza and the West Bank.

The strength of books such as Orientalism (1978) and Culture and Imperialism (1993) lay in the fact that they, despite their breadth of analysis, are founded on this specific historical experience, that they have this as a soundboard. That said, these books, and the thinking out of which they grew, confront Western positions and the Western canon. But the author is entirely consistent here as well. Said, who grew up in the Western educational system, is in a position to open up Western thinking precisely because of personal experience at the periphery. Working his way through his own experience in the Middle East, he revolutionizes both our view of the West and our self-conception.

The aim of Said’s project is to take seriously the humanism and universalism that have been preached by the West, and to point out their significance for our understanding of the world. This is an attempt to open up the West in order to establish its ability to talk with Palestinians, Arabs, and other groups.

As mentioned earlier, the strength of Said’s thinking consists in the fact that it has been nourished by concrete historical experience, while at the same time, guiding and teaching us to pay attention to injustice, asymmetries of power, and their attendant representational strategies generally. Said is interested in present conflicts and how they articulate themselves in space. Yet they cannot be comprehended without the historical dimensions inscribed in them. Indeed, Said is not interested in historical constructions that are isolated from contemporary human experiences.

Said revealed the Orient–Occident dualism to be a Western historical construct and thereby helped us to reorder the geographies of our world. Today, this, in effect, helps us to recognize that the dividing line between the poor and the rich, between the powerful and the marginalized, is not the Mediterranean, but that it runs through societies both north and south of the Mediterranean. True, large parts of the Arab population have been forcibly excluded from public political participation in their respective countries, but the de-democratization process in societies north of the Mediterranean is alarming as well. Driven by the logic of the financial markets, which have been removed from democratic control, new asymmetries have emerged between northern and southern Europe, but also within all European societies.

A chief question that Said’s work poses in this situation is: how can a voice be given to those who are pushed to the margins in these processes? Our exhibition “After Year Zero” (2013) can serve as a further historical reference point for this challenge. The project went back to the image of the “zero hour”—which had stood for German history’s new

References:

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hegel/#BacIdeUndGerTra

(9http://www.michel-foucault.com/concepts/)

http://journeyofideasacross.hkw.de/out-of-academia-in-places/bernd-m-scherer.html

Said, E. (1978) Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books.

Said, E. (1994) Jane Austen and Empire. In: Culture and Imperialism. London: Vintage Books, 95–116.